Iran’s Proxy War Moves South: Somaliland Enters the Houthi Threat Map

Houthi threats against Somaliland mark Iran’s effort to extend proxy pressure beyond Yemen and closer to the Bab el-Mandeb’s strategic chokepoint.

Houthi media has pivoted hard toward Somaliland. The de facto Shura Council speaker declared Somalia essential to Houthi security, a buffer zone they intend to defend. Abdul-Malik al-Houthi threatened military strikes against any Israeli presence. State media calls Israeli diplomatic engagement “the Zionist dagger,” a blade positioned across the strait, aimed at their flank.

But it’s worth pausing to ask: what do Iran and its most capable remaining proxy actually want from this?

Not the stated goal. The strategic function. Because Somaliland sits directly across from the Bab el-Mandeb. If the Houthis can credibly threaten any Israeli foothold there—military, intelligence, or diplomatic—Tehran gains leverage over one of the world’s most critical chokepoints without deploying a single asset of its own. The Houthis do the threatening; Iran collects the strategic dividend.

Which means this isn’t really about Somaliland. It’s about finding a new pressure point—another angle on the Red Sea, another way to encircle the Saudis.

And the timing tells you everything. This week, Tehran’s crackdown on protesters has reportedly passed 5,000 dead, with doctors inside Iran, in the few reports escaping the internet blackout, estimating the toll to be far higher. Foreign Minister Araghchi warned Iran would be “firing back with everything we have” if attacked. The regime needs external threats to amplify. It needs its proxies performing. Assad is gone. Hezbollah is degraded. The Houthis are what’s left, and they’ve found a cause that pays dividends everywhere that matters.

On January 7, Iran’s Foreign Ministry condemned Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar’s visit to Somaliland, calling it “an illegal step that infringes on Somalia’s sovereignty and territorial unity.” Tehran demanded collective action from Islamic and African states.

Let’s be clear about what this is. Iran doesn’t care about Somali sovereignty. It has spent decades undermining sovereignty across the Arab world through precisely the kind of proxy networks it’s now activating. What Iran cares about is preventing any Israeli strategic foothold near the Bab el-Mandeb. And it needed a vehicle to translate that concern into a threat.

Eight days later, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi delivered the amplification. In his January 15 speech commemorating his brother Hussein’s death, he converted Iranian diplomatic objections into an explicit military threat. He mocked Sa’ar’s visit as a “sneaking operation” through Ethiopia, conducted “without any prior announcement,” his aircraft allegedly disabling its transponders, attributing this secrecy to fear of the Houthis. Not the broader Arab world, which he dismissed as posing no concern to Israel:

“It’s clear the criminal Sa’ar was afraid of the Yemeni position. The level of the Arab and Islamic position doesn’t frighten him.”

When Houthi officials say “Yemen,” they mean themselves. The conflation is deliberate. This is the messaging sweet spot the Houthis have perfected: positioning themselves as the only actor Israel takes seriously while dismissing the broader Arab world as complicit through normalization, irrelevant through inaction. It flatters the domestic audience, humiliates regional rivals, and serves Iranian interests simultaneously.

Then came the threat:

“We are serious about targeting any Israeli presence in Somaliland... any military base or the like, any fixed Zionist presence we find accessible to us, we will not hesitate to target militarily.”

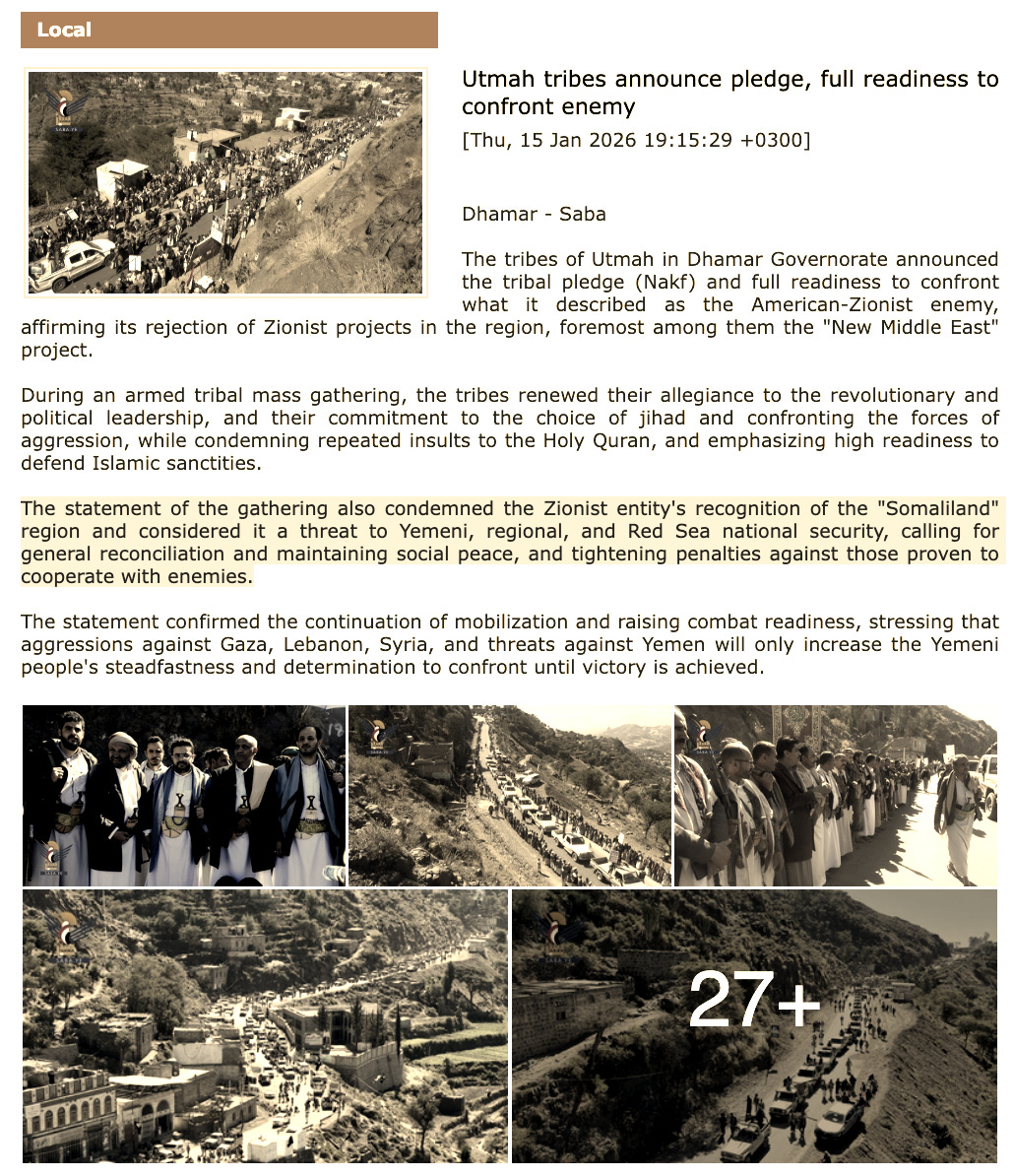

By January 20, the directive had been fully absorbed into Houthi state media. The military-affiliated 26 September newspaper published an editorial reframing Israeli engagement as “a direct and real threat striking at the heart of Yemeni national security.” Houthis also pushed the Somaliland framing across multiple arenas, weaving it into tribal pledges, mobilization events, and loyalty displays to ensure the message circulates well beyond formal media channels.

This is what matters: the Houthis don’t need to actually strike anything in Somaliland. By saturating their media with the claim, by declaring it their concern, they’ve already accomplished the strategic goal. They’ve inserted themselves into a geography that matters to Tehran, extended their relevance beyond the Red Sea, and made themselves indispensable to the network at the precise moment Iran is losing assets everywhere else. The threat is the product. Whether they ever act on it is almost beside the point.

The choice of Somaliland is strategic in another sense. By opposing Israeli engagement with a breakaway region, the Houthis wrap themselves in a cause that resonates far beyond their movement: anti-fragmentation, sovereignty, resistance to outside meddling. Arabs, Muslims, African Union members who oppose secession can see themselves in this framing. The Houthis get to appear as champions of a principle when what they’re actually defending is their position on a chokepoint.

This is what makes it dangerous.

What distinguishes the Houthis from other Iranian proxy relationships isn’t military capacity. It’s ideological infrastructure. When Assad fell, Iran lost not just a strategic partner but much of its ideological foothold, because Assad’s relationship with Tehran was ultimately transactional, maintained through state apparatus rather than popular movement. The Houthis represent something more resilient: an ideological project that Iran has successfully grafted onto existing grievances and tribal structures. They’ve built not just military dependency but a worldview that reproduces itself—through schools, through media, through the daily machinery of social control.

So when Tehran faces contraction on every front, internally and externally, this is what remains: not territory, but the capacity to manufacture enemies and mobilize against them.

Iran cannot project conventional power to the Horn of Africa. It cannot diplomatically prevent Israeli engagement with Somaliland. But it can signal to its most capable remaining proxy that this geography now matters, and the Houthis, who have spent years demonstrating willingness to act on such signals, will handle the rest.

This is how ideological proxy systems survive strategic contraction: by detaching from territory and reattaching to threat narratives. The geography shifts; the function remains.

It’s worth remembering the sequence. In September 2022, Mahsa Amini died in custody, and Iran erupted. Thirteen months later, the world’s attention was on Gaza. The protests had been crushed, and a new crisis, one that served Tehran’s interests, consumed the international bandwidth. Whether that timing was strategic calculus or convenient coincidence, the regime benefited either way. The gaze shifted.

Now the protests have returned, larger and bloodier than in 2022. And once again, the Houthis are performing on cue, new geography, new cause, new reason for the world to look anywhere but Tehran. There is no evidence of direct orchestration, but the pattern is consistent, and it keeps paying dividends.