From Captagon to Gaza in 24 Hours

The U.S. Embassy Posted a Cartoon about Houthis’ Trafficking in Drugs. The Houthis Made It About Gaza.

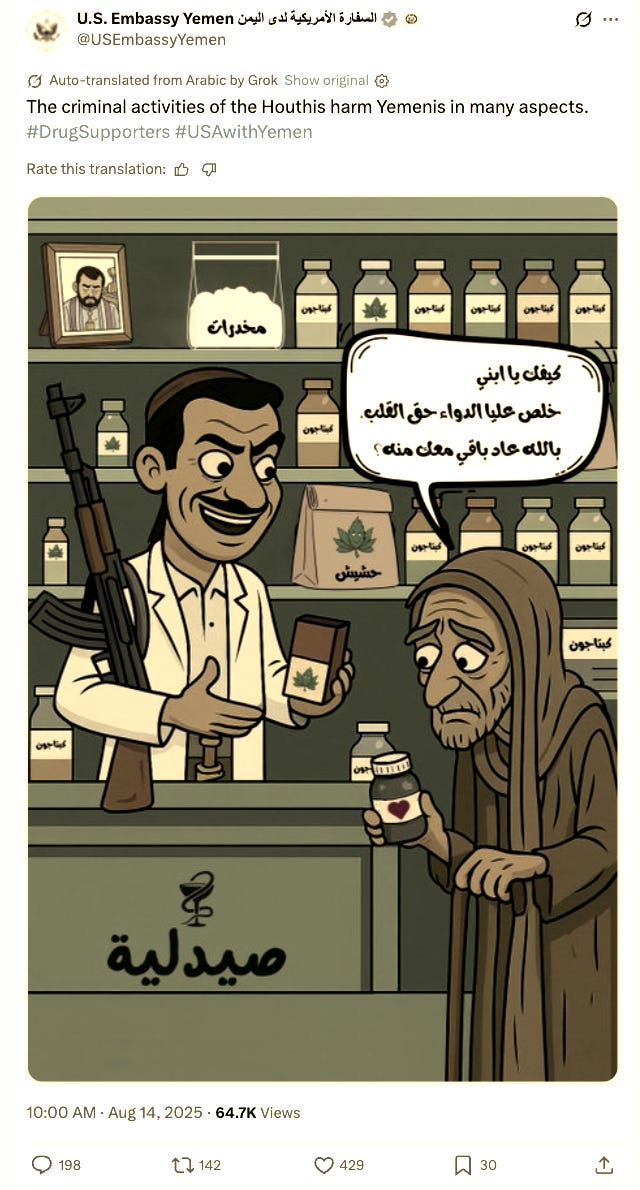

On August 14, the U.S. Embassy in Yemen posted a cartoon on X. The image was crude but pointed: An elderly man asks a pharmacist for heart medicine. Instead, he is offered narcotics by a smiling militant with a Kalashnikov slung across his back. The caption tagged with #Ansar_Narcotics, a play on Ansar Allah ('supporters of Allah), recast as Ansar Narcotics ('supporters of drugs').” The message was obvious: the Houthis have become drug traffickers, profiteers in the Captagon trade.

This was the U.S. Embassy's own attempt at public messaging; a crude, AI-generated cartoon image, but deliberate communication designed to expose the Houthis. The U.S. Embassy wasn't wrong about the substance; the Houthis have been deeply enmeshed in narcotics trafficking, particularly the lucrative Captagon trade. Left on its own, however, the AI-generated cartoon would probably have garnered a few reshares and disappeared into digital noise. But within twenty-four hours, the Houthis made it clear that they were watching.

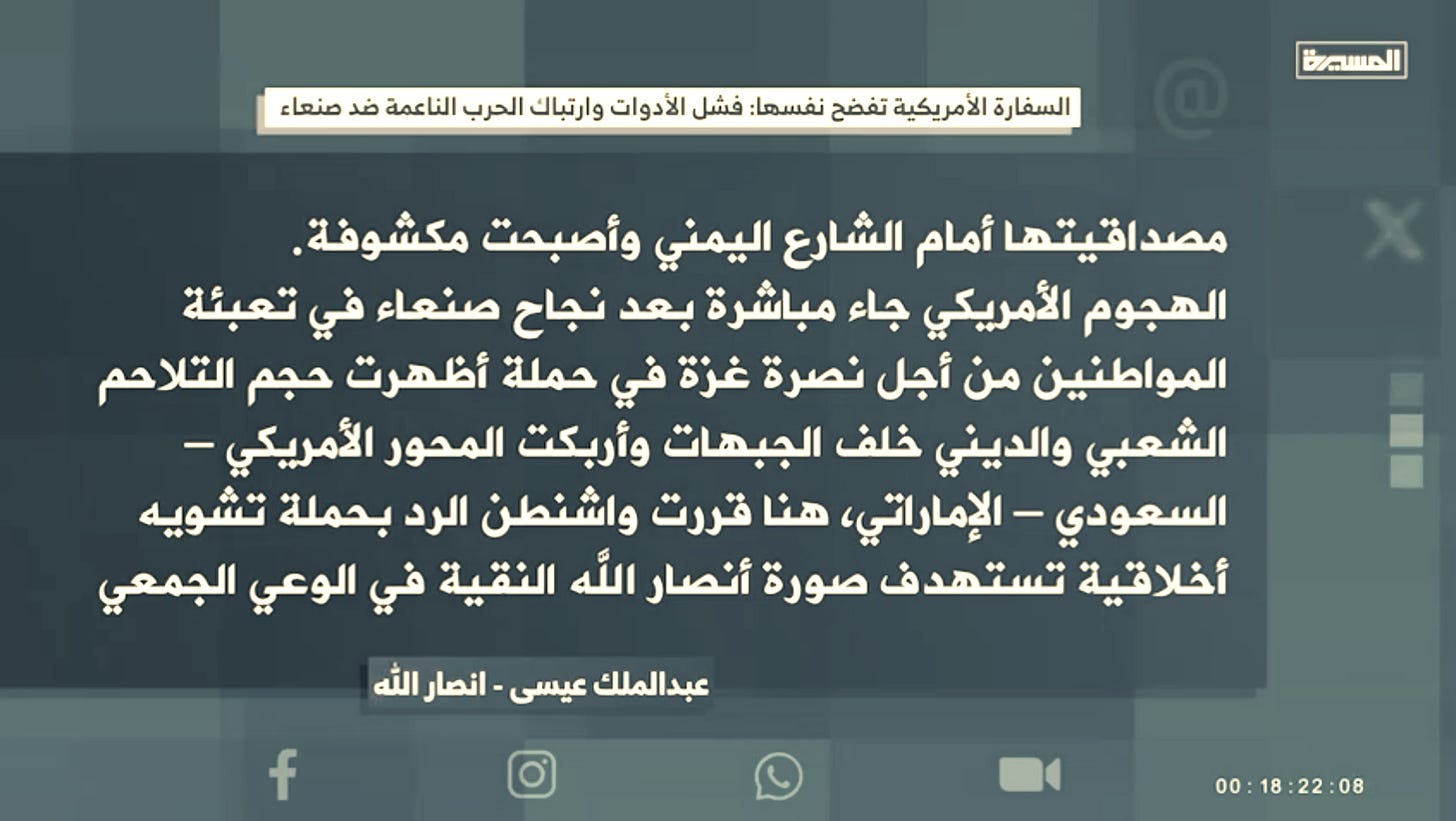

A critique appeared on their official website (Ansar Allah), authored by Abdelmalek Issa and titled “The American Embassy Exposes Itself: Failure of Tools and Confusion of Soft War Against Sanaa”, and covered by Houthi media TV broadcast channels, including al-Masirah. This was no ordinary respondent. His professional title -Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at the University of Sanaa- may suggest scholarly objectivity, but Issa is reportedly the brother-in-law of Abdelmalik al-Houthi, the movement's leader. His blood ties confer legitimacy, a reminder of how family and ideology fuse in movements like the Houthis.

Issa's article reframed the U.S. Embassy's cartoon entirely, not as a jab about drugs but as an act of "psychological war" by "the Great Satan's embassy." Washington, he argued, was in crisis. It had lost faith in its "local agents," whom he identified as NGOs, media outlets, and civil society activists who had all failed to sway Yemeni opinion. "When the sponsor speaks," he declared, "it means the tools have died." The implication was clear: these alleged agents had become so ashamed of their association with a discredited sponsor that they abandoned America, forcing the embassy to do the work itself. His phrasing served double duty: it portrayed all local critics as foreign mercenaries while elevating the embassy's cartoon as proof that America had been forced to intervene directly. In propaganda logic, the very act of U.S. communication with the Yemeni public became an admission of defeat.

From there, Issa turned to Gaza. He constructed a narrative where the embassy's cartoon was timed in retaliation for Yemen's mobilization in support of Palestine. Only days earlier, Sanaa had orchestrated mass campaigns of solidarity with Gaza and against the disarmament of Hezbollah, revealing what he called the "religious and popular cohesion" of Yemeni society. Of course, measuring popular opinion is remarkably easy when dissent is met with detention or worse. In his logic, Houthis' success had unnerved Washington and its Gulf allies. And as proof, the clinching evidence was a statement from Abu Ubaida, spokesman of Hamas's al-Qassam Brigades, who a month earlier had praised Houthis as "إخوان الصدق" or "brothers of sincerity." That endorsement, Issa argued, struck fear into Washington. The cartoon, from his point of view, was nothing more than a petty reprisal: America lashing out not because of drugs, but because Yemen had been elevated in the eyes of the Palestinian resistance.

This is the broader Houthi strategy: Gaza as alibi. Every criticism gets laundered through Palestine until it disappears. Captagon trafficking? A smear meant to punish Yemen for standing with Gaza. Economic collapse? A price paid for loyalty to Gaza. Repression and prisons? Necessary to safeguard Gaza’s cause. By collapsing every grievance into Palestine, the Houthis turn the Palestinian struggle into a universal shield, one that deflects scrutiny, sanctifies their abuses, and recasts any critique as a betrayal of the resistance

To solidify his argument, Issa wove Qur'anic verses throughout. "They wish you would compromise, so they would compromise" (68:9). "If good touches you, it distresses them; if evil befalls you, they rejoice" (3:120). Each verse served as divine subtext: America's attempts to smear the Houthis only proved its own moral corruption. For Issa, every insult was proof of virtue, every slight divine confirmation of Yemen's righteousness.

And then came the key phrase: the embassy's cartoon, he said, was part of a "soft war" (حرب ناعمة / harb na'ima). The Houthis are intimately familiar with this term, having deployed it against their own enemies, but it isn't homegrown—it's imported directly from Hezbollah and IRGC lexicons. For nearly two decades, Iranian leaders from Khamenei to the IRGC have used it to describe Western attempts to subvert the "resistance front" through culture, media, NGOs, music, and even satire. Iranian hardliners have warned of "soft war" to explain everything from student protests to Hollywood films. Now the Houthis repeat it almost verbatim, repurposing Iran's political theology for Yemeni conditions. Therefore, a U.S. embassy cartoon becomes not a jab at narcotics, but an assault on "Qur'anic awareness.”

The choice of messenger underlines the point. Issa is both kin and intellectual. His blood tie to the leader ensures the message carries family legitimacy. His professorship lends a scholarly aura. But this reveals Yemen's tragedy: the University of Sanaa, once a fragile beacon built with Gulf support from Kuwait and allowing some measure of intellectual freedom, now functions as a node in the broader propaganda apparatus. Professors produce ideological treatises instead of scholarship.

The timeline tells the story: cartoon posted, leader's brother-in-law pens rebuttal, rebuttal amplified on Al-Masirah, Gaza invoked, Qur'an quoted, Iran's "soft war" lexicon deployed. Within a day, the original allegation, drug trafficking, had vanished. In its place stood doctrine: America is desperate, Yemen is righteous, Gaza proves it, Abu Ubaida confirms it, scripture sanctifies it.

For the Iran-backed Houthis, provocations, no matter how small, cannot be left alone in this system. They must be absorbed, reframed, and returned to the public as affirmation. In Tehran, in Hezbollah's Beirut, and now in Houthi-controlled Sanaa, the process is identical. A cartoon becomes evidence of holy war. An op-ed becomes liturgy. A university becomes a factory for ideological reproduction.

On the surface, this was a spat over a drawing. In reality, it revealed the machinery of narrative control now shared across an entire axis. Every provocation is reprocessed into proof. Every insult becomes doctrine. Every external challenge becomes another brick in the wall of ideological certainty.

In this system, complexity dies. A cartoon about drugs cannot simply be about drugs; it must be psychological warfare. America cannot have mixed motives; it must be purely desperate and evil. Yemen cannot have both legitimate grievances and real problems with trafficking; it must be entirely righteous. The erasure of ambiguity itself becomes the goal, leaving no space for the messy contradictions of actual reality.

As I reflect on this, a line from a book once gifted to me by a friend and former mentor, Marta Colburn, has stayed with me. In a footnote, she quoted G Wyman Bury from the early 20th century: 'The Yemeni is not fanatical. He has his own religious views, but realizes, from the sects into which his own people are divided, that there are at least two sides to every religious question.'

For those growing up under the Houthis rule today, that is no longer the case.